Author - Sajad Rasool

Sajad Rasool supervises Kashmir Unheard, an independent community news platform in the conflict area of Kashmir. Sajad is an Acumen India fellow, 2019 | Fellow at Reporters Without Borders, Berlin Scholarship program, 19 | Fellow at Seeds of Peace.

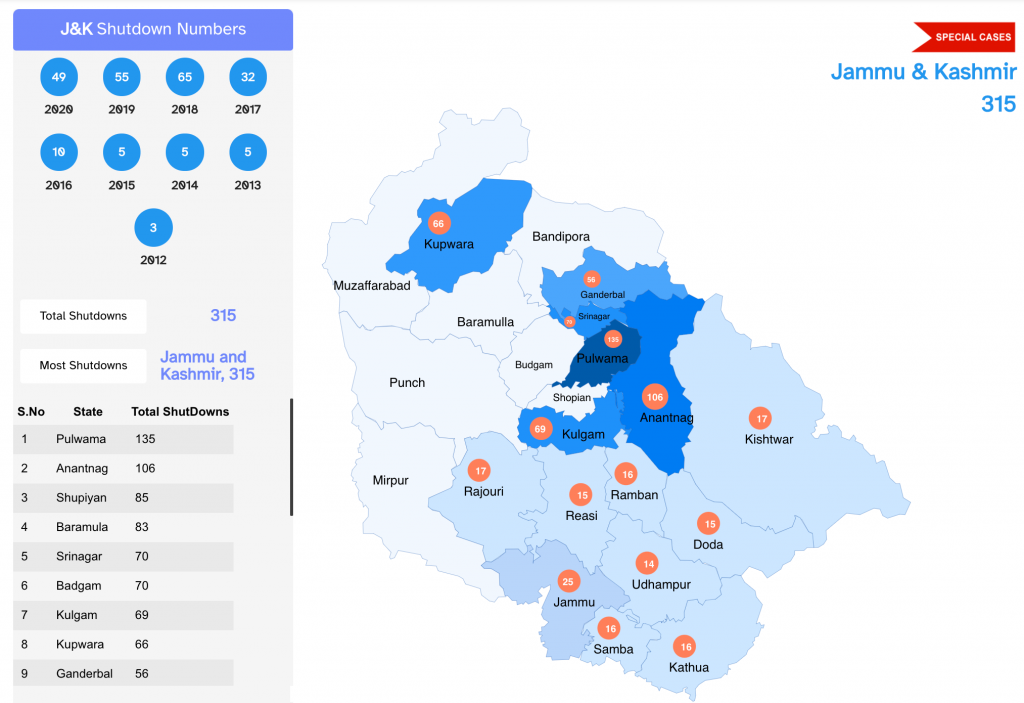

On the morning of 5th August 2019, Kashmir woke up under a siege. Mobile networks, landline phones, and internet access were completely shut down, and police barricades increased even more than usual. The valley of Kashmir, which was already the most militarized zone in the world with armed military personnel for every seven civilians, was now turned into a large prison after an additional 28000 troops were deployed. Initially, we thought it would be just another extended internet shutdown, a common occurrence in Kashmir that saw state-imposed internet shutdown for more than 134 days between August 2019 to 2020, the longest internet shutdown in any democracy so far. With the onset of social media post-2009, the Internet emerged as one of the best tools for local Kashmiris to share their opinions, concerns, and issues. Social media platforms, for the first time, offered space to Kashmiris to give voice to their own issues, rather than depend on mainstream Indian or Pakistani news reporters to represent them. The Abrogation of Article 370 and more than four months of internet blockade that followed brought the local press under total control of the state. What followed was a nightmare for news reporters, journalists, and freelancers. Local Kashmiri newspapers didn’t publish for months, staff was laid off, news blogs were not able to produce news for months. Freedom of speech and press is difficult to protect when there is absolute media control, regular internet shutdowns, and above all too many guns around. These two years of abrogation of Article 370 saw extreme pressure from the Indian agencies and police on journalists. Journalists have been summoned to local police stations for writing news stories in Indian or International media outlets as far back as 2016.

This month, local J&K police conducted raids in the houses of four journalists in Srinagar. Not only were their personal digital devices, such as laptops, mobile phones, and tablets confiscated but the mobile phones of their children and other family members were taken away as well. This suggests the violation of basic rights to privacy and free speech of ordinary civilians. Internet shutdowns are routinely used to suppress local stories and narratives of the excesses committed by the Indian state. The story of Kashmir and its ordinary people is always muzzled in narratives set by the news studios in Delhi, except for a few local journalists working for the Indian mainstream press whose reporting remains influenced by editorial policies of media houses they work for. Earlier last year, three journalists were booked by local police under terror laws. Some journalists report this harassment to the press, but others prefer to remain silent. In the month of August, I spoke to one of my teachers, who had written a piece on Kashmir for an international publication. A few days later he was called to the police station in Srinagar and questioned for hours, but decided not to report the incident of harassment to the media fearing further reprisal. Even the journalists who write for Indian newspapers are often questioned. This method, adopted by the Indian state in Kashmir to curb media freedom, has led to the local scribes finally doing self-surveillance on what to write and what not to write.

There is a pattern in here, the Indian state is using all the methods to silence Kashmiris and their voice. Its agencies don’t bother to rebut the story carried by the press or shared on social media, instead, they choose to use all their might to suppress. Using draconian laws like UAPA, where an individual has to prove himself/herself innocent adds to the story. UNHRC chief, Michele Bachelet, in her recent statement has called the use of UAPA in Kashmir, where the highest number of cases have been filed, “worrying”. The use of UAPA against human rights defenders has been widely criticized by journalists, academics, and activists across India. Campaigns for the release of activists booked under this law and the scrapping of UAPA have been gaining steam in recent months. Democracy and such laws cannot go hand in hand, they are contradictory to the very idea of democracy. Legal experts in India have been raising questions about this law and hinting towards India becoming an ‘Orwellian regime’. Yet such campaigns rarely feature the names of Kashmiri journalists detained under this law. It has been three years now that Asif Sultan of Kashmir Narrator continues to be in jail. Sultan is accused of sheltering militants. However, there are speculations that he has been detained for writing an article on Burhan Wani, a young militant commander killed in 2016 by Indian forces.

In Kashmir, every Kashmiri is extremely cautious about what they write and share on social media. A simple post can land them in jail. This has led to increasing distrust in the social life of people. These tactics have been referred to as psychological warfare as well, with an increase in mental health cases over the last two years. Experts have called it a catastrophe. Every time something happens in Kashmir, between India and Pakistan, hundreds of young boys are picked up and sent to jails in the name of mitigating security threats. One of my friends who is a brilliant Urdu poet has been writing poetry about life in Kashmir and sharing it on social media for many years. He was arrested in the middle of the night by the army and special operations group and later tortured for the crime of writing poetry.

The right-wing Hindutva BJP led govt has been glorifying their decision of stripping Kashmir of its partial autonomy and has been building a narrative that Kashmir is now on its path to development. Mainstream media has been used to not only popularise this false account but also to demonize the ordinary Kashmiri. It might appear that the media and people in Kashmir are free to report, voice themselves, but reporting the truth and facts is different.

The Internet has been the only means for the Kashmiris living across Europe and other places to stay in touch with their families and get news updates. However, frequent shutdowns of the internet have increased the agony of this tiny population spread across the continents. While India’s Minister for Information and Broadcasting, Prakash Javdekar claims that the press in India enjoys ‘absolute freedom’, muzzling of press freedom in Kashmir prevents the emergence of authentic reports from the ground. Reporters Without Borders, in its 2021 report on Press Freedom Index, while ranking India 142nd out of 180 countries, lower than Myanmar, which recently saw a military coup, also called India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi the ‘predator of press freedom’. These critiques indicate the use of state power and resources to curb the truth, hide the facts and manipulate the narrative. India continues to be the leader in internet shutdowns worldwide. The frequent blockades not only affect journalists, but common people like business owners, students, and other essential spheres of life such as healthcare. It is an approach that punishes ordinary Kashmiris while the state kickstarts its colonization project by issuing around 4.1 million domiciles to non-Kashmiris and opening access to Indian business tycoons to invest in Kashmir.

Despite the display of a positive image of Kashmir’s development and tourism post-August 5 2019, evidence shows that normalcy is being forced at the behest of military might. Journalists and human rights defenders are being harassed, questioned, and summoned to police and military stations for writing news articles, reports, and producing video stories, while the internet continues to be monitored for activity deemed objectionable by the state.